Elizabeth Price

13.05.2023 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Diane Mullin

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 12.04.2019

Flickering lights, techno dance music and monotone robo-talk emanate from the shrouded Perlman Gallery at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Upon entering the cave-like space, the viewer is enveloped by two towering moving-image works, displayed on opposite walls. Although the artist, Elizabeth Price, identifies FELT TIP and KOHL (both 2018) as distinct works of art, they work together to slowly pull in the viewer, as their almost biomorphic or telematic connections become increasingly apparent. The voiceover, sound and imagery differ in each, but at times the rhythm of the music in one seems to physically stimulate aspects of the other, as when pictured branches in KOHL begin to sway in rhythm to FELT TIP’s beats. This is all in keeping with the artist’s belief in the sensory power of her medium. She explains that she thinks of moving image – especially video– as something you ‘experience sensually as well as something you might recognise’.1 In other words, this work does not just ‘sit on its ass in a museum’, as Claes Oldenburg famously celebrated in 1961.2

In this manifesto of sorts, Oldenburg calls for an art made from ‘anything in one’s surroundings’, for ‘art that embroils itself with the everyday crap’, from underwear to the meows of cats. Price emphasises the time-based and theatrical qualities that animate her moving image work, using terms such as drama, flow and surge, and yet it is the artist’s embrace of ‘anything’ as material that is the key to understanding her art. After all, the idea of big beautiful images as sensory seems obvious and well-trod territory. The aesthetic of the two works, specifically their use of colour, repetition, overlays and scaled overlays of archival and new images, are grounded in the advertising, design and propaganda that make up the contemporary visual landscape. Price’s mode of address is sardonic, closer in tone to the critical, feminist position of Barbara Kruger than the joyful, liberatory – if somewhat ironic – inflection of Oldenburg’s New Realist and Pop Art compatriots of the 1960s.

It is the 1970s and 1980s from which Price mines much the source material for her historical musings. FELT TIP, the taller, narrower work, comprises images of felt-tip pens – especially their nibs – and of men’s fabric ties from those decades FIG.1. ‘Ties are not simply phallic’, Price asserts, but symbolise, together with the pen, a new order of late capitalism, since ties ‘echo the pen-nib itself, signifying the way executive labour expresses its power: through writing’. Images of details of textile necktie patterns, felt-tip pens FIG.2 and moving images of dancing female legs in heels appear and disappear in time with the soundtrack. Like all the artist’s works, FELT TIP is physically and conceptually grounded in its location. The Perlman Gallery, which houses the works, is a soaring new two-storey space that was created by a cannibalisation of the museum’s former director’s office – a history that provided the basis of the film’s white-collar subject. In the museum’s archive, Price found photographs of the Walker’s offices from 1971, taken in the newly constructed building by Edward Larrabee Barnes. The shiny executive suite of white desks with nothing on them inspired the artist to contemplate this new administrative class in a map of post-war economy and society.

KOHL, the other work in the space, is presented on four screens arranged horizontally, and highlights images of the industrial working class. Historical photographs of coal rigs at mines in the United Kingdom appear in colourful arrays FIG.3, tiled like Andy Warhol’s electric chairs, Marilyns, superstars and later wealthy socialites. Like the photographs of the original Walker Art Center offices, the oil rig images were unearthed in archives, in this case from the National Coal Mining Museum in Wakefield. Taken by the amateur photographer Allen Walker (no relation to the museum’s founder), the blown-up photographs are animated with sound, text and other images, including swaying branches and pools of water. The sequences are again keyed to the tempo of the soundtrack, transforming this unknown photographer into a superstar of sorts. Through the austerity of the rig images, the work clearly evokes the hardship of mining and also its unfortunate environmental consequences, formally emphasised by the landscape format of the screens.

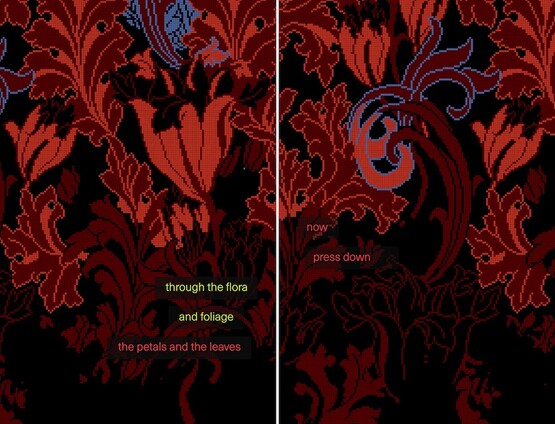

In addition to the visual array and coal-related sound-bytes, Price also offers a presumably fictional sci-fi narrative – in an early ‘digital’, pixel typeface – of beings known as ‘Visitants’ that lurk and move across the giant field of underground waterways running between the rigs FIG.4. Mixing historical documentation and fabrication, it is unclear whether these are images of real rigs. Is the story of the Visitants an implausible local fable, or is it based in reality? All that Price has found, hoarded and manipulated FIG.5 in her films is presented on the same plane, unsettling the hierarchy of truth versus fiction. It takes time to connect the dots.

Price uses what she describes as a scattered, intuitive collecting practice, which through continual looking and thinking gives rise to surprising visual and historical overlaps (as she calls them) between the objects, images and ideas. Interested not in discrete objects or subjects, but in the way one thing can be connected to another, she collects her materials through intuition: ‘So I gather things, in waiting, in the hope of finding another thing that might connect to it in unexpected and reciprocally revealing ways’.3 She explains she works primarily by ‘piling up’ images and other things on the timeline tool of digital software. She then finds a way to organise what she’s gathered ‘through the connective process of editing’.

In this way, Price offers editing as producing. This perhaps recalls what we know of in art history as ‘subtractive’ sculpting – the way sculptors carve form out of a mass (of stone, clay, whatever). It also, however, evokes a Dada-like chaos and Surrealism’s enthrallment with chance, in Price’s case through the kaleidoscopic lens of computer software. This is, in the end, maybe Oldenburg’s anything amplified up to everything. If one connects to related online magazines (like the Walker’s), YouTube videos or Wikipedia entries, and then follows the hyperlinks embedded there, the ways into this work for the viewer seem endless. This, it seems Price asserts, is a good thing. One thing is for sure, this work definitely does not just sit on its ass in the museum.

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

8th December 2018–1st March 2020

Nottingham Contemporary

16th February–6th May 2019