Interpreting Oscar Murillo

by Isaac Nugent

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 30.05.2019

‘No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main [. . .] never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee’. Lines taken from John Donne’s Meditation XVII (1623) are affixed to the wall above the ramp that leads down to the main galleries of Oscar Murillo’s exhibition Violent Amnesia at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. Although these words are printed in bold and evenly spaced vinyl, it takes a moment to register the quotation because the text has been partially obscured with swathes of white household emulsion, so that the letters appear to dissolve into the white of the gallery wall FIG.1. This forceful erasure of Meditation XVII illustrates our propensity to forget the meaning of Donne’s words: all too often we fail to recognise our common humanity and overlook the suffering of others, particularly those living in less developed parts of the world.

The exhibition title speaks to this collective process of forgetting, within which the artist has a unique perspective. Having been born in Colombia but brought up in London, he is acutely aware of the privileges he has enjoyed relative to his friends and family in Colombia. The works that constitute this show, including paintings, wall hangings FIG.2, arrangements of found objects and a sound piece, are Murillo’s response to the anxiety this privilege causes him. Clearly, they emerge out of an energetic studio practice. Often the artist seems to physically assault his materials, channelling raw emotions of anger and dislocation. Many of the painterly marks that end up on Murillo's canvases and wall hangings could only be the product of considerable force. One of his found objects, a set of church pews, has even been attacked with an axe FIG.3.

The artist’s gestural approach makes for an animated response to the world and the problems that it faces, but not always a coherent one. Coming down the ramp into the body of the exhibition, several sheets of canvas seeped in black paint, unevenly sewn together and hung from the ceiling, bisect the room and block any onwards trajectory FIG.4. This messy intervention into an otherwise pristine white gallery space forms part of an ongoing series of works entitled The Institute of Reconciliation (2014), a further manifestation of which also fills the floor of the Sackler Gallery, the largest of the exhibition spaces at Kettle’s Yard. Here, uneven piles of canvas, again steeped in black paint, are scattered across the floor FIG.5. The far wall has been soiled with black marks, as if pieces of the canvas had been brushed vigorously against it. It takes several interpretative leaps in order to ascertain what Murillo might mean to achieve through these two iterations of The Institute of Reconciliation. The term ‘reconciliation’ implies the action of making two things compatible, or a return to good relations after a period of estrangement. Perhaps Murillo proposes to find rapprochement between the different aspects of his own identity, as a product of both Colombia and Britain, or to resolve differences between cultures more broadly. For two installations principally comprised of material soaked in black, it is also impossible to avoid an association to mourning and loss. Recalling once again the title of Murillo’s exhibition, it is perhaps the artist’s intention to remind us that, for reconciliation to be achieved, we must recognise the suffering of others and remember what they have endured.

Needless to say, not all visitors to Violent Amnesia will make the connection between investigations into the potential of canvas seeped in black paint and the artist’s anxieties about global inequality. They may simply enjoy the physical properties of Murillo's work: delighting in the intensity of the artist's mark-making and uninhibited use of materials. The raw smell of paint still pervades the gallery speces, indicating that some of the pieces are not yet dry. It is as if the artist has only temporarily stopped painting and could return to add further marks to them. Whether making objects in two or three dimensions, Murillo does not seek to resolve the final appearance of his compositions; they remain provisional, in a state of flux.

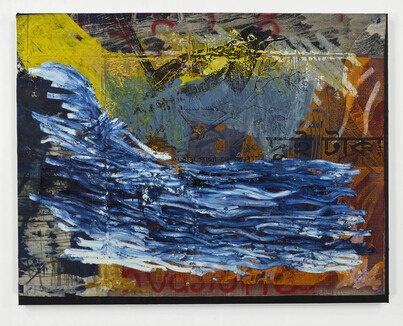

An unfinished aesthetic has a certain allure of its own, but for Murillo this way of working seems to have greater significance, reflecting the unstable nature of the world around him. Whether driven by conflict or attracted by opportunity, people now move between different parts of the world in larger number than ever before. Many attempt to cross borders illegally, enduring considerable hardship as a result. Three paintings hung in the Sackler Gallery highlight the issue of migration through the includion of screen-printed images of birds FIG.6. Perhaps Murillo chooses to include this motif because birds have the freedom to migrate seasonally across the globe, irresepctive of borders they cross in the process. Humans, however, are limited by the construct of nationality, arbitrarily restricted in where they can and cannot travel. Other aspects of these works might be used to develop this analogy further: the paintings themselves are created out of several pieces of canvas, stitched together in a haphazard manner. The stitching could represent the way in which we divide ourselves into different geographical entities. The birds are themselves often overpainted with swathes of thick oil paint. They could be understood to be caged in by the strokes of Murillo’s brush, just as we are confined within the boundaries of the countries that we belong to.

The second of the main gallery spaces at Kettle's Yard is hung with paintings from the artist’s Catalyst series FIG.7. These are different in character to the rest of the works included in the exhibition. Created via a less direct method of working, they emerge from a process akin to monoprinting, a rudimentary printmaking technique. A ‘master’ canvas is laid on the floor and saturated with paint before a second canvas is placed on top and paint transferred between the two using a broom handle. What results from this idiosyncratic procedure are canvases filled with a web of marks, recording the frenzied movements of the broom handle across the back of the second canvas. Since Murillo cannot see how his painting is developing while making it, the final appearance of each work in the series is somewhat accidental. The process seems to be more important than the outcome here: the intense periods of physical activity through which works from the catalyst series are produced act as a kind of therapy, perhaps Murillo's means of dealing with the anxieties he feels about the state of the world.

Catharsis, the release of strong emotions through creative activity as a means of coming to terms with an issue and resolving it, is a particularly good word to describe both the motivations behind the Catalyst series and the exhibition as a whole. Making work appears to be a personal form of catharsis for Murillo, and visitors to this exhibition are invited to share in his grief and join him in seeking reconciliation. Violent Amnesia is a call to collective catharsis, encouraging us not to overlook the suffering of others any longer.