Steve McQueen

by Sarah Bolwell

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 14.05.2020

The current survey of Steve McQueen’s work at Tate Modern – which has closed its doors early due to the COVID-19 crisis – ostensibly picks up where the last survey left off. Remarkably, given the artist’s international standing as both artist and film director, this was over twenty years ago, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, in 1999. The display contains fourteen video works and one slightly anomalous 24-carat gold sculpture, displayed in the near-darkness of a nightclub. Although this appears fairly modest for a Tate retrospective, the collective duration of the works is almost four hours, to which visitors could add a significant percentage of time spent queuing between screens.

Two films are projected in the central atrium. The first, Static (2009), is a seven-minute aerial shot of the Statue of Liberty in New York FIG.1. The camera circles her and the noise of the helicopter borders on offensively loud. The sound of the blades becomes like static from a radio; the feedback plus the shaky camera makes for a dizzying uncomfortable experience. The second, Once Upon a Time (2002), is a looped projection of images selected by NASA to represent life on Earth to extra-terrestrial life-forms, set against a soundtrack of Glossolalia.

There are no new works on display; Steve McQueen’s Blue-chip representation has meant regular gallery exhibitions of his work over the years,1 alongside his burgeoning career as a Hollywood film-maker. It is the balance of these two approaches to image-making and a deep investigative attitude about his adopted medium that makes McQueen so singular. And something that persists in both his video works and feature films is a preoccupation with the darker elements of the human condition. Be it shame, hunger, death, pain, pleasure or slavery, McQueen’s subjects are universal in their appeal.

McQueen’s occupation of the uneasy hinterland between cinematic film and video art prompts questions of definition: not necessarily what it is that we are watching, but rather how do we watch? While acknowledging cinema's mainstream function to translate narrative, McQueen's films also test our human faculties as viewers. In Exodus (1992/97), the earliest film in the show, for example, objects drift in and out of focus, a red London bus grabs our attention one second, followed by a flash of green on our periphery, a sound distracts us the next, in much the same way as visual and aural elements might in real life. The action hints at narrative in that we are presented with characters and context, but here, for McQueen, sound and image are more than just the formal elements of the medium, they are protagonists, while character and plot are perhaps supporting actors.

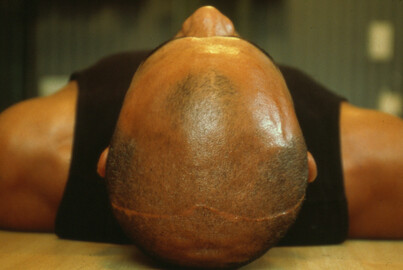

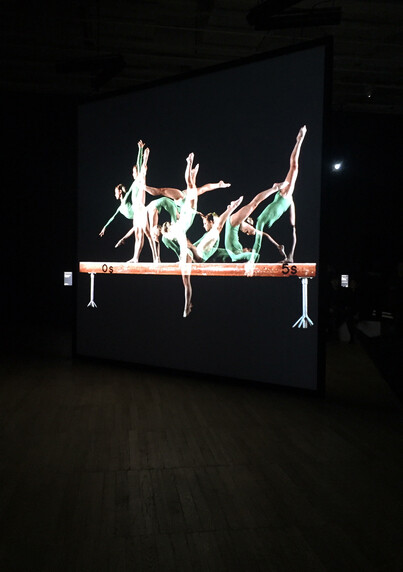

In some capacity all his films interrogate this interplay between sound and image. Some are exclusively visual, as in Cold Breath (1999), in which McQueen tugs and rubs his own nipple for ten increasingly uncomfortable minutes, while others such as 7th Nov (2001), a monologue by McQueen’s cousin about his accidental killing of his brother FIG.2, take the form of oral testimonials. McQueen confidently deconstructs our understanding of the medium. Once Upon a Time, for instance, is essentially a slideshow with a backing track, illustrating that all films are comprised of a series of stills. Many of the images incorporate an element of time-telling: the trajectory of a gymnast’s cartwheel on a bar is annotated on top of the still in seconds FIG.3. The slideshow/the images are found objects – fabricated by the American government as a diplomatic telegram to alien civilisations, a brief introduction to life on earth. How exactly NASA expected life-forms from another galaxy to interpret these images (technologically as well as contextually) remains unexplained, but they highlight the limitations of the purely pictorial communication of information in single static images. The unintelligible soundtrack shows the limitations of aural communication too.

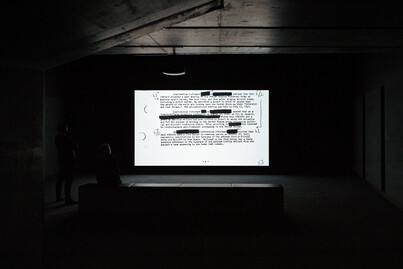

While McQueen prioritises the formal qualities of film for his audience – listening and looking – his films are also rich in content and allusion. Static, for example, exploits the symbolic power of the Statue of Liberty, with its historic associations from the American dream to the 9/11 attacks in 2001. McQueen does not shy away from the political. End Credits (2012–ongoing) FIG.4, for example, takes the form of scrolling FBI reports on Paul Robeson, an African-American singer, actor and Civil Rights activist investigated in the 1950s for his associations with the Communist party. These reports are read by an expressionless female voice but out of sync with the visuals, which produces a disjointed viewing experience. The word ‘redacted’ is used to verbalise the redacted words and passages in the reports, its repetition such that the word loses meaning, becoming a rhythmic, almost abstract, element.

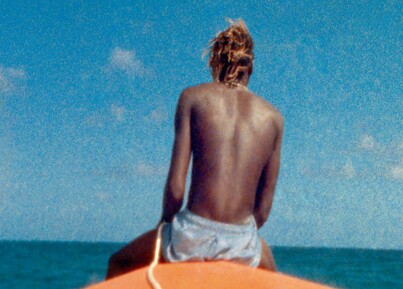

Ashes (2002–15) is McQueen’s most evocative balance of filmic styles. Recorded on two separate visits to the island of Grenada where some of the artist’s family still live, the film follows the story of a young man, known as Ashes. The first screen is a harmony of pulchritudinous colour, the golden brown of a young fisherman’s skin set against an orange canoe and the blue ocean FIG.5. The scene is simultaneously soporific and exalting: water laps at the boat, Ashes smiles. On a second screen a longer, narrative film is projected, which, through snippets of interview with islanders, stories the death of Ashes twelve years on in murky, drug-related, circumstances. His death is not sensationalised but expressed through the mundanities of the building of Ashes’s tomb, including the engraving of the headstone. Through these activities the viewer is party to the family’s grief, a process that transcends culture, continent and class.

Across the river at Tate Britain, McQueen’s photographs are on view as part of The Year 3 Project FIG.6. Working with ArtAngel, McQueen invited 1,500 London primary schools to collaborate on the project, photographing over 76,000 students from year 3, in class pictures with their teachers. McQueen was roughly this age (eight to nine) when he was first introduced to art on a school visit to the Tate Gallery. The project, he says, both encourages young people to visit the gallery (present pandemic circumstances excepted) and provides a glimpse of the ‘future in the present’.2 The images were also posted on billboards around the city, encouraging discussion of this question in the collective quotidian.3 As a Black Londoner, McQueen wanted to insert himself into the narrative of art history, not relinquishing his alterity, but engaging with the pervasive question of what it is to be British.