At the height of second-wave feminism in the 1970s, the writer and experimental film-maker Laura Mulvey wrote a manifesto that continues to echo throughout feminist theory and women’s moving image practice to this day. In ‘Visual pleasure and narrative cinema’ Mulvey called for the patriarchal narrative structure of cinema – characterised by the ‘male gaze’ – to be replaced with a radical film-making ‘to free the look of the camera’ and destroy the ‘voyeuristic active/passive mechanisms’ of classical narrative film.1 Many of the contributors to Women Artists, Feminism and the Moving Image have been influenced by Mulvey, who has also written the preface for this volume. The artists whose work is discussed here are Mulvey’s heirs but are also responding to a new world of images and image-making. Edited by Lucy Reynolds, this substantial anthology includes contributions from curators, artists, academics and activists. Their descriptive and analytical case studies, which focus on avant-garde or experimental films, videos and multimedia pieces by female artists, explore women’s lives, work and political activism.

The terms of the book’s title are fraught and suggest a distinction between feminist theory and women’s artistic practice. ‘Woman film-maker’, for example, can be limiting in terms of marketability and artists often avoid it, but as Melissa Gronlund notes, the idea that ‘gender should be legible [. . .] is a founding tenet of this book’ (p.245). She suggests the term now refers to advocacy in the face of continued ‘gendered under-representation’ (p.247). How many male film-makers are listed in monographs or gallery catalogues as ‘male film-makers’? How many female film-makers have had monographs or solo shows? Gender itself has become increasingly complex and individualised, and feminism, with its own history, is employed here variously as methodology, advocacy, discourse and activism.

As Reynolds notes, advances in technology have expanded and influenced the directions of moving image. The turn to video in the late 1970s led to a divergence between artists who continued to work with the materials of film and those who chose video for documentation, for example, the recording of performance art. This created ‘two modes of practice with different communities and forms of endorsement’ (p.4). Moreover, those who write critically about artists’ moving image are ‘caught at the interstices between cinema and art’s different cultural discourses’ (p.6). The anthology is arranged into three sections: one focuses on history and lesser-known artists or works, the second section emphasises the ‘corporeal’ register and the third, perhaps the most contemporary, provides an overview of the field and also looks at public reception and audiences, most notably in the contexts of class and race. Each section opens with a conversation between curators and film-makers, balancing the immediacy and authenticity in these less formal exchanges with academic essays.

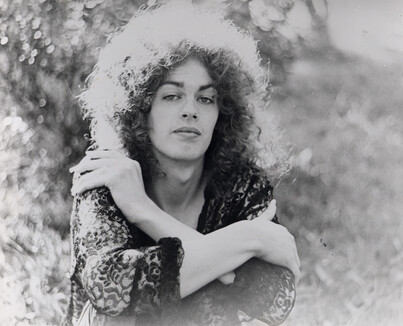

Recurring themes across these sections draw from feminist history, theory and practice. Among several exciting (re)discoveries is Elinor Cleghorn’s discussion of Lotte Reiniger’s silhouette films from the 1920s FIG.1, which identifies issues that women artists still encounter, such as being excluded from exhibits or funding, and the relegation of women’s art to ‘craft’. The writer, curator and activist So Mayer’s analysis of Julie Dash’s short film Four Women (1975) is one of several articles to recoup a little-known work and to employ intersectional analysis, dealing with the experiences of women artists of colour. Other intersectional studies include May Adadol Ingawanji’s examination of the Vietnamese artist Nguyen Trinh Thi’s experimental films that combine footage from pre-War Vietnamese feature films with newly created material FIG.2 FIG.3. Rachel Garfield looks at film-makers from the United Kingdom’s diasporic and immigrant communities in the 1980s, and Maria Walsh discusses issues of class and race in two films that share the theme of women’s solidarity: Lucy Beech's Cannibals (2013) and Rehana Zaman's Some Women, Other Women and all the Bittermen (2014). In these works, artists confront the creative questions but also negotiate their subjects’ positions as ‘other’. This may also be said of the writers and artists in the volume who identify as lesbian, queer or transexual, and speak enthusiastically of the community and activism related to their identity. Surprisingly, however, only one of the essays here discusses a film that focuses on non-cisgender identity: Erika Balsom’s essay on Penelope Spheeris’s I Don’t Know (1970) FIG.4 – a pioneering film for its time.

An essential theme for women film-makers is the image of the female body, identified by early feminists as the fetishised object in patriarchal narrative film, and a number of women film-makers remain conscious of the ‘woman as spectacle’.2 Cate Elwes surveys work from three generations of feminist film-makers and their shifting use of the female image: at various points they have chosen to be invisible in their films, appear only partially, use surrogates or use only their voices. Mulvey herself is an exception to this in her two ‘theory films’ made thirty years apart, in which, as Catherine Grant describes, she ‘reads to the camera’ (p.62) – an ‘enunciation’, to use Janet Bergstrom’s term, with face and voice.3

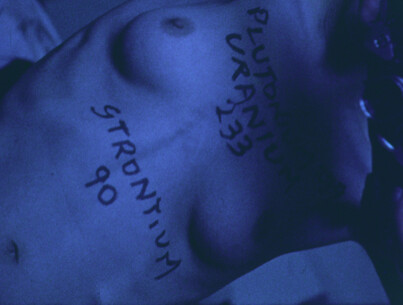

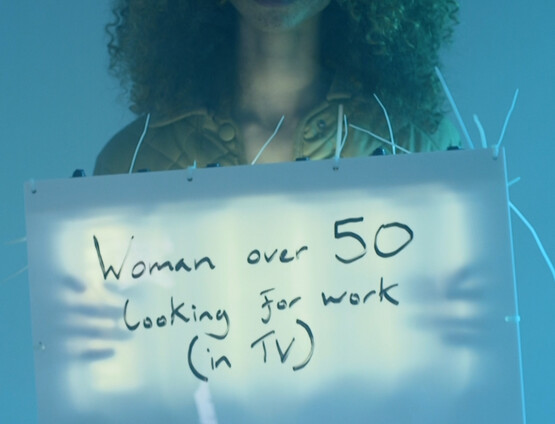

Elsewhere the female body is both document and metaphor. Maud Jacquin provides an unflinching description of Sandra Lahire’s films from the 1980s that disrupt cinema’s eroticism FIG.5. Here, Lahire’s body becomes a site of her struggle with anorexia; in later ‘anti-nuclear’ films from this period her naked ‘overexposure’ refers both to the effects of radiation on women’s bodies and to ‘the light’s inscription on celluloid’ (p.130). Sarah Neely and Sarah Smith examine Rachel Maclean’s ‘ventriloquy’ while her body appears almost unrecognisable due to make-up, costume and digital manipulation FIG.6 FIG.7. Maclean’s projects satirise the objectification of the female body and the pressure on girls and women to look physically ‘beautiful’. Neely and Smith argue that Maclean also addresses the labour involved in women’s ‘production of the self as brand’ (p.172).

Feminism and film practice coalesce in the conversation between feminist curators that opens the final section of the book. Discussion ranges from equal opportunity for women artists, curators and workers, to strategies to reach younger audiences. Helena Reckitt describes meetings in which she teaches working people ‘strategies’ through the works of feminist film-makers – educating and informing ‘from outside the Anglo-American feminist canon’ (p.181).

The conclusion of this dense, abundant collection inspires by looking back at gains made in feminist theory and women’s moving image, while also looking ahead to activism and outreach, especially in support of marginalised women. However, here we must note absences in the book: are there truly no moving image works that address violence against women, poverty or homelessness? These conditions are experienced disproportionately by the women that the contributors express a desire to reach. Fascinating as the studies in this collection are, these omissions may lead the reader to recall the inequalities that plagued second-wave feminism, and to wish to learn more about moving image work that is created by or addresses marginalised women today.