Hollis Frampton: Photographs

by Anne Breimaier

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 26.11.2020

The American artist and art critic Hollis Frampton (1936–84) is best known for his experimental films, which were honoured during his lifetime with retrospectives at such renowned institutions as the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1973), the Knokke Experimental Film Festival, Knokke-Heist (1974), and the Anthology Film Archives, New York (1975). In recent years, an awakened interest in Frampton’s work with still images has been demonstrated by a number of solo exhibitions as well as research by a second generation of scholars and curators, who address his multi-media practice beyond the imperative of his films.1 The presentation of Frampton’s photographs at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London (Goldsmiths CCA), which spans a period from the late 1950s to the mid-1980s, marks a promising chapter in the rediscovery of the artist’s work with photography, from a curatorial as well as a scholarly perspective.2

As a retrospective, the show at CCA picks up where Bruce Jenkins and Susan Krane left off in 1984 with their influential exhibition of Frampton’s photographs, xerographs and collages.3 Hollis Frampton. Recollections / Recreations had been developed with the artist before his untimely death that same year and began its tour of the United States at the Albright-Knox-Gallery, Buffalo. The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue with a list of carefully researched references hidden in Frampton’s images, ranging from Flaubert’s The Temptation of St. Anthony (1874) to action painting and Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–23). Flaubert’s novel provided the title for a corresponding series of black-and-white photograms from 1962 FIG.1, also exhibited at CCA, which produce fluid patterns that resemble the abstract permutations in his film Palindrome (1969).

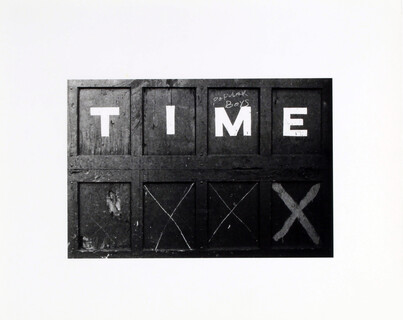

The exhibition includes works from a range of Frampton’s early photographic series. The Secret World of Frank Stella (1958–62) comprises situational portraits of the painter in the streets of New York and in his studio FIG.2, whereas the images from Junk and Rubble (1961–62) were made ‘in the ruins of Bleeker Street’.4 Also on show are three images from Frampton’s Word Pictures series (1962–63) FIG.3, photographic cut-outs found in New York’s cityscape that anticipate the use of street signs and other instances of notational iconicity in his 1970 film Zorns Lemma. These early series can be perceived as traces of the artist’s investigations into his time, his place and its past. This included the history of photography, a medium that, at the time, was still widely associated with a Modernist aesthetic or journalism, and according to Frampton, devoid of a critical tradition. His writings on Eadweard Muybridge, Edward Weston and Paul Strand, published throughout the 1970s in such leading magazines as Artforum and October, must therefore be regarded as a critical enterprise that strongly informed his work as an artist photographer.

Whereas in his art criticism Frampton investigated the work of iconic photographers, in his own imagery he aimed to point out ‘clichés in method and seeing’,5 creating ‘riddles’ or ‘puns’ for the viewer.6 His references to protagonists of the history and theory of photography through strategies of resemblance must therefore be understood as secondary to his goal to create ‘a most meaningful (image) structure that is most meaningful to the intellect’.7 Frampton’s practice thus anticipated a generation of cultural practitioners, such as Douglas Crimp or Sherrie Levine, who inherited a similar critical attitude towards Modernism’s picture-making conventions, which resulted in the need to address ‘representation as such’.8

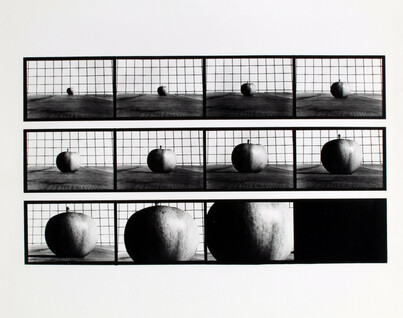

Frampton’s recursive approach is demonstrated in the images of Junk and Rubble, which ironically refer to the tradition of Weston’s iconic object studies of urinals, peppers and nudes, while a blurry Stella pictured from behind in a washtub quotes the bathing Picasso photographed by David Douglas Duncan for Life magazine in the late 1950s. The three images from Word Pictures are reminiscent of Dorothea Lange’s photographs of billboards and street signs in rural America during the Great Depression. For the series Vegetable Locomotion (1975), made together with Marion Faller, the artists employed zucchini, cabbage and apples from their garden to reference Muybridge’s studies of moving bodies, which were first published in 1888 FIG.4.9 Muybridge’s photographic fragmentation of the animated, however, is rendered absurd by the actions that Frampton and Faller perform with the unanimated.

The exhibition at CCA supports a way of looking at Frampton’s early photographs as appropriations avant la lettre. To this effect, it has recently been argued that his attitude towards his artistic ancestors should be understood as one of revision rather than succession. The show also indirectly addresses one of the major challenges facing Frampton scholarship today, which is the retracing of a formal development within his conceptual practice involving photography, not only within an American context.

Much like his early films, Frampton’s photographs from the 1960s are certainly testament to the struggle of a young artist in New York City trying to find a voice in an art ecology that he felt was inherently hostile to his interest in questioning photographic illusion.10 However, Frampton’s late conceptual series, such as ADSVMVS ABSVMVS, In memory of Hollis William Frampton, Sr., 1913–1980, abest (1982), dedicated to his late father, and Rites of Passage (created with Marion Faller between 1983 and 1984), leave much room for speculation about how his practice could have developed further conceptually.

The fourteen colour photographs in ADSVMSV ABSVMVS depict a series of specimens, plants and animals FIG.5, which allude to an abundance of references, some of which are seminal works in the theory of photography and film, such as William Henry Fox Talbot’s Pencil of Nature (1844) or André Bazin’s ‘L’ontologie de l’image photographique’ (1945). The twenty black-and-white images that make up Rites of Passage, on the other hand, create a tableau of middle-class rituals of consumerism and convention, featuring variations of the same wedding cake, which only differ from each other in their toppers FIG.6. They are reminiscent of visual investigations into the properties of societal conformity at the time, such as Dan Graham’s conceptual project Homes for America (1965).11

These late photographic series by Frampton are crafted ‘copresences’, ‘contending for the center of the spectatorial arena’, ‘supreme fiction, which parses sets of spaces in favor of successiveness’,12 in which ‘image and language trespass in each other’s house’.13 Their traditional arrangement at eye level in the exhibition space at CCA invites the visitor to experience the temporal, spatial and tactile capacities of photography FIG.7 FIG.8. It can thus be understood as a congenial gesture by the curator of the exhibition, that while moving between the photographs on display, visitors can listen to a set of files preserved at Harvard Film Archive of Frampton’s work in time-based media, performance and music, accessible via QR code.14

Confronting the viewer with performance and sound this retrospective at CCA frames Frampton’s photographs not as mere prints on a wall or decisive moments captured of curious specimens, but as instructions for their own reception in a world so ‘full of still photography to kill every one of us a hundred times over’.15 It not only grasps the 1960s didactic gist of Frampton’s images but also provides an introduction to his visual politics at large. As such, it may also work to promote a better understanding of his influence on a contemporary generation of artists, such as the late curator, performer and educator Ian White.16