Monstrous spectacle

27.10.2021 • Reviews / Exhibition

Ithell Colquhoun is remembered as that rarity: a woman Surrealist. She is also well known for the book The Living Stones (1959), her esoteric love letter to West Cornwall. By the time she died in a Cornish care home in 1988 she had vanished from public view for, as Amy Hale notes in her introduction, ‘she didn’t know how to promote herself’ (p.16). Over the last twenty years Colquhoun’s concerns and feminist magical practices have become increasingly popular: two biographies have been published, her archives and pictures have been acquired by Tate and her books are in print again.1 Art historians, neopagans and feminists have come to the fore and are digesting the nourishment and novelty of her offering. Women connected to witchcraft and earth studies identify Colquhoun as a priestess, including Hale, who dedicates this book ‘to all the women magicians, past, present and future. May our stories continue to be told’.

Although the theme of magic runs throughout Colquhoun’s practice, she was capable of simultaneously developing so many theories and lines of inquiry that anyone setting out to write about her is obliged to do the same. Hale, an American anthropologist and writer ‘specializing in the occult, the esoteric and other liminal people, places, and things’,2 stumbled upon Colquhoun during a period of student research in the fields of paganism, earth studies and ethno-tourism in West Cornwall. She describes her book as an ‘ethno-biography’, made possible by a Paul Mellon Fellowship that enabled her to travel from the United States and spend time sifting through Colquhoun’s inchoate paper archive.

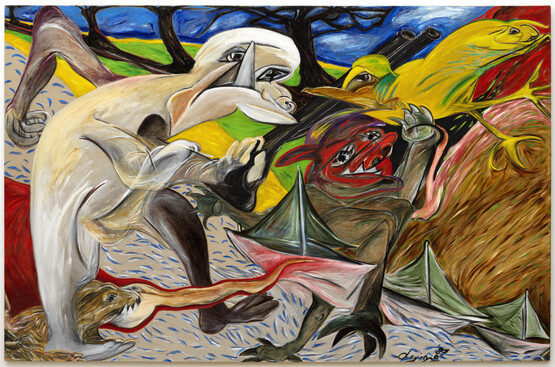

Born in 1906 in Shillong, India, Colquhoun was comfortably middle class; she was educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and later attended the Slade School of Fine Art, London, where she won prizes. By the age of twenty-four she was already fascinated by theosophy and alchemy but preoccupied by Surrealism most of all. She was photographed by Man Ray in Paris and attended Salvador Dalí’s famous lecture delivered in a diving suit and helmet in 1936. Dalí inspired her spate of little-known paintings that easily rival his work of the time: woman as landscape in Scylla FIG.1, a pair of tumescent rock knees part submerged in a nacreous marine world, and the hyper-sexualised skeletal male figure colonised by sea creatures, cryptically titled from a poem by Baudelaire, Gouffres Amers FIG.2. By 1939 she was exhibiting with Roland Penrose and sitting at André Breton’s feet to imbibe the concept of ‘psychological morphology’ or autonomism – art made without conscious control. From this point on, Hale notes, Colquhoun’s ‘Surrealism and her occultism truly begin to support one another’, and magic became her nexus for everything. Returning to Cornwall she tuned into the psychic zones of the landscape to make paintings such as Dance of the Nine Opals FIG.3. Ostensibly representing a local stone circle and its origin myth, its elements come from ‘actual’ and ‘potential’ worlds: nine is the number of creation in Hermetic philosophy, opal was Colquhoun’s birth stone and the standing stones are supersensual energy conduits drawn, as the artist wrote, from ‘some hinterland of the mind [. . .] built from several impacted strata of material and meaning’.3

Gradually, Hale maps out this singular ‘thin blond sexy woman with unusual, slightly bulging eyes and a love of nude sunbathing’, who habitually broke boundaries and taboos and who painted hundreds of explicit erotic watercolours to elucidate the theories she was devising about sex magic while rejecting lovers and close human relationships FIG.4. She collected initiation and universal wisdom traditions; she embraced, but then left, artistic groups and magical circles. Her constant questioning of assumptions surrounding the nature of women and gender ‘in magic, spiritual attainment and societal evolution’ (p.61) hums in the background like radio static, vigilantly monitored by Hale.

Hale corrals her material into three chapters under the headings of Surrealism, Celtism and Occultism. Each is self-supporting but for many, Celtism – the romantic lure that brought the painters Gluck and Marlow Moss and so many other seekers to Cornwall’s western tip – will be the most accessible and compelling. Colquhoun claimed a Celtic ancestry that afforded her second sight, visions and otherworldliness. ‘When the war was over and I could partially escape from my own entangled life, it was to this region, this “end of the land” with its occasional sight of the unattained past, that I was drawn’, she wrote in The Living Stones.4 Colquhoun’s Romantic Celtism synthesised beliefs and fringe intellectual currents concerning sacred sites, such as megalithic monuments, ancient churches and stone crosses FIG.5. She was an early adopter of Michael Theory, coining the term ‘Michael-force’, the alternative sacred archaeology that maps power spots and reservoirs of the earth’s magnetism that acted as conductors to a higher consciousness. The theory was taken up by such notable Earth Mysteries devotees as Julian Cope and John Michell, the author of The View over Atlantis (1969).

Although Colquhoun despised incomers, she nevertheless practised the self-consciously ‘simple’ life of a second-home owner, buying a tin hut in the Lamorna Valley in 1949. Here she experienced the psychic shifting of landscape and time, wrote her treatise on autonomism The Mantic Stain, and resolved to move to Cornwall permanently.5 In 1959 she published The Living Stones, her chronicle of the indigenous and the ‘other’, which detailed the animism of running water, tree spirits and sacred stones that were portals between past and present. She wrote of how folk customs that were ‘scraps of ceremonial magic, smelling of incense and the midnight oil of the adept’s study, have drifted down haphazard to the rustic sage, to be mingled with a maternal lore redolent of the hay-field and cow-byre’.6 Hale’s title, Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, is taken from this paean to the genius loci of Lamorna.

However, as Hale concludes, ‘Colquhoun did not live in a time that supported who she was. She didn’t have a network that would nurture her capacities and there were no platforms for a voice so strong and resistant’ (p.219). Hale’s most dense research lies in her long, specialised section on Colquhoun’s highly individualistic occult practice: her restless intelligence that mapped the similarities between Eastern and Western magical systems, Tantra, Kabbalah, the tree of life, heterodox Christianity and the sacred feminine. Hale describes a woman increasingly out of kilter, feverishly seeking new pathways to the supernatural truth. From the 1950s to 1970s she experimented with the occult organisation Order Templi Orientis, druidism, joined the Holy Grail Masonic Lodge and was ordained as a Priestess of Isis. She also undertook ‘softer’ mindful practices: she recycled rubbish into art, one example is her repurposing of a plastic fruit tray to form the breasts of the fertility goddess Diana of Ephesus in Ephesian Diana (1967). Using an automatic process, she made tree drawings as offerings for the White Goddess and as antidotes to the wasteful technology damaging the planet. She proselytised against the ‘enslaving’ designs of women’s clothing, even offering to do a radio commentary on the topic for the BBC. Her agile intellect could conjure sex magic and poetical folklore. Hale’s academically rigorous yet sympathetic study brings her back, like Persephone, from the underworld of an unwarranted oblivion.